All being good it looks like I’ve secured employment for a tiny while longer. Hooray!

The place I’m moving to is a big place for synthetic colloids, so it seems like a good time to go through what I know about colloids. If nothing else it’ll be interesting to compare this to what I’ll know in a year’s time! So, here is a theorists perspective on colloid science.

I’ll spare the usual introduction about how colloids are ubiquitous in nature, you can go to Wikipedia for that. The type of colloids I’m interested in here are synthetic colloids made in the lab. They’re usually made from silica or PMMA (perspex), you can make a lot of them, they can be made so they’re roughly the same size and you’ll have them floating around in a solution. By playing with the solution you can have them density matched (no gravity) or you can have them sinking/floating depending what you want to study.

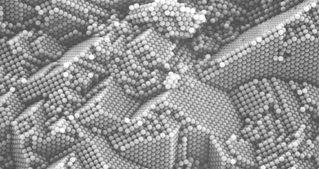

The colloids that people make sit nicely in a sweet spot of size and density that make them perfect for testing our fundamental understanding of why matter arranges itself in the way it does. Colloids can undergo most of the same phase transitions that we get in molecular systems, but here we can actually see them. Take for example this beautiful electron microscope image of a colloidal crystal from the Pine group at NYU.

1. They’re big enough to image

Colloids are usually of the order a micron across. At this size it is still possible to use confocal microscopy to image the particles. While nothing like the resolution of the electron microscope, the confocal can actually track the positions of individual particles in real time, in solution. It’s almost like a simulation without the periodic boundary conditions! A confocal can take lots of 2D slices through the sample, such as below from the Weeks group. The scale bar is 5 microns.

If you do it quick enough then you can keep track of the particle moving before it loses its identity. The Weeks group did some very famous work visualising dynamic heterogeneity in liquids near the glass transition. (see their science paper if you can).

If we want to think about colloids as model atoms, which we do, then there’s another property apart from just their size that we need to be able to control.

2. You can control their interactions

Being the size they are, if we didn’t do anything to our colloids after making the spheres they would stick together quite strongly due to van de Waals forces - this is the attraction between any smooth surface to another, as used by clingfilm. To counteract this the clever experimentalists are able to graft a layer of polymers around onto the surface of the colloid.

It’s like covering it with little hairs. When the hairs from two particles come into contact they repel, overcoming the van de Waals attraction. The particles are “stabilised”. In this way it’s possible to make colloids that interact pretty much like hard spheres. So not only can we use them as model atoms, but we can use them to test theoretical models as well!

Further to this the colloids can be charged and by adding salt to the solvent one can control the screening length for attraction or repulsion to other colloids. Finally there’s the depletion interaction. I want to come back to this so for now I’ll just say that by adding coiled up polymers into the soup we can create, and tightly control, attractions between the colloids. With this experimentalists can tune their particles to create a zoo of different behaviours.

3. They’re thermal

If the colloids are not too small to be imaged, why not make them bigger? If we made them, say 1cm, then we could just sit and watch them, right? Well not really. If you filled a bucket with ball bearings and solution, density matched them so they don’t sink or float and then waited, you’d be there a long time. The only way to move them in a realistic amount of time is to shake them - this is granular physics.

Granular physics is great but it’s not what we’re doing here. Real atoms are subject to random thermal motions and they seek to fit the Boltzmann distribution. For this to work with colloids they need to be sensitive to temperature.

When a colloid is immersed in a fluid it subject to a number of forces. If it’s moving then there will be viscous forces, and on an atomistic level it is constantly being bombarded by the molecules that comprise the fluid. In the interests of keeping this post to a respectable size I can’t go through the detail, but suffice it to say that this is an old problem in physics - Brownian motion.

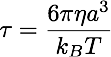

Under Brownian motion the large particle will perform a random walk that is characterised by its diffusion constant. The bigger this number the quicker it moves around. A more intuitive number is the time it takes for a particle to move a distance of one particle diameter. When you solve the equation of motion for a large particle in a Stokesian fluid you find that this time is given by

where  is

viscosity, a is the particle diameter, and k_B T is Boltzmann’s

constant and temperature. Now this does get more complicated in dense

systems and the properties of the fluid matter, but this is a good

start. This could be a topic for another post.

is

viscosity, a is the particle diameter, and k_B T is Boltzmann’s

constant and temperature. Now this does get more complicated in dense

systems and the properties of the fluid matter, but this is a good

start. This could be a topic for another post.

For a typical colloidal particle, around a micron in size, you have to wait about a second for it to move its own diameter. For something only as big as a grain of sand you can be waiting hours or days. Even by 10 microns it’s getting a bit too slow. But close to 1 micron, not only does it move about in an acceptable time frame, we can easily track it with our confocal microscope. If it’s diffusing around then we can hope that it will be properly sampling the Boltzmann distribution - or at the very least be heading there. So once again, that micron size sweet spot is cropping up.

So what else?

Hopefully this serves as a good starting point to colloids. Obviously there’s a lot more to it. An area that I’m very interested in at the moment is what happens when the colloids are not spheres but some other shape. I’ll be posting more about it in the coming months.

If you don’t remember anything else just remember that colloids are the perfect size to test statistical mechanics and to be visible.

So well done colloids, you’re just right size.